It’s my impression that professional archaeologists are enthused about “single-component sites” because the story is simplified if there’s only one culture represented in the record. There’s no mixing of artifacts and consequently less confusion about what artifact goes with what cultural group. On the other hand, “multicomponent sites” can be exciting because there’s evidence that the same site has been used time after time by diverse and distinctly different cultures over a long stretch of deep time.

Lone Tree Farm is one of these intriguing “multicomponent sites”. However, it may be more accurate and interesting to think about it as an ancient campsite (Jones, 2022) which is a concept from Indigenous traditions. That is, it is a place to which people have returned for countless generations over many millennia. There is evidence that people have lived and traveled along Kanaranzi Creek for thousands of years.

Although the possibility of a “multicomponent site” was raised during the initial geophysical investigation on the Farm, the true depth of the time record only emerged when the full set of projectile points was evaluated. That work was done by Dr. Phyllis Johnson and the staff at Augustana University’s Archaeology Laboratory. Basically, we turned our collections over to them and they provided professional interpretations of the significance of site 21RK82 on Lone Tree Farm.

Figure 1----Projectile points and the interpretations of their estimated ages. Illustration from Johnson (2023).

As I described in the first post of this series, four or five generations of kids in the Shurr family have spent time down in the pasture looking for arrowheads. But, it’s only been the last decade or so that the Creek has shared it’s memories. Someone in the first three generations (we’re not even certain who it was) found a fairly large oblate projectile point (Figure 1: B-1) and brother Bob found a smaller one with a very distinct arrowhead shape (Figure 1: C) in the 1960s. In the past few years, we’ve found half a dozen more. The archaeologists from Augustana measured them all and identified the lithic material that they were made from. One distinctive material (Figure 1: A-1) called Knife River Chert came all the way from central North Dakota. The experts also classified the various types based on other projectile points found in other areas. Recognition of characteristic types provided a handle on just how long a span of time is recorded in these memories. And it’s a l-o-n-g time….. like more than 12,000 years!

Archaeologists use projectile points to “tell time” in about the same way as geologists use guide fossils (Google it, for more details). Certain distinctive fossils are found in sedimentary rocks that have been dated using radioisotopes. So, when the fossils are found in a different rock layer in a different area, we can estimate a date for this new occurrence. That’s pretty much how the arrowheads are used by archaeologists. Specific types are found in association with datable material, so when the distinctive arrowhead is found in another area we can infer an age range. In archaeology it’s usually a carbon radioisotope that provides the number.

Figure 2----Diagram showing the relative ranges of the projectile points shown in Figure 1.

A diagram illustrating the relative ages and overlaps for our arrowheads is shown in Figure 2. Most of the letters refer back to the specific types shown in Figure 1 and there are roughly three different clusters. The first cluster is projectile points A-1 and A-2 that date back to about 8,000 BC or “Late Paleoindian/Early Archaic” in technical terms. That’s almost back to the Ice Ages! B-1 and B-2 are included in a wide range of dates, but C, D, and E overlap and cluster in a period of about 0 to 4,000 BC or “ Middle to Late Archaic” in technical terms. So, there’s a gap of about 4,000 years in the memories preserved by the arrowheads. Still, there’s a record of people living and traveling along Kanaranzi Creek for a very long time! And, they probably all had distinctive and unique cultural attributes.

The letters F and G on Figure 2 constitute the third cluster and refer to Great Oasis and Oneota cultures respectively. They aren’t documented directly by the arrowheads but do represent specific “slices” of time. Notice that there’s only about 1000 years separating the second and third cluster. A piece of pottery indicates that the Great Oasis culture may have existed along the Creek (Dale Henning, personal communication). However, the evidence for an Oneota presence is much less direct and ties the Farm to Blood Run. The people who lived at Blood Run 30 miles to the east may have also lived and traveled along Kanaranzi Creek.

Figure 3----Blades (technically known as “bifaces”) made of Bijou Quartzite. A) The two blades shown at their full size. B) Microscopic close-up of a blade edge. Illustration slightly modified from Johnson (2023).

The possible connection to Blood Run is based mainly on the two distinctive blades made of Bijou Quartzite (Figure 3-A) that our grandchildren found along the Creek. Bijou Quartzite is an exotic lithology that comes from south-central South Dakota and the elongate blades made of Bijou are common in collections made at Blood Run (Henning and Schermer, 2004). It is a relatively soft material that has unique knapping qualities and isn’t used for many other artifacts than the elongate blades. The folks at the Augustana Archaeology Lab examined the edges of the blades using a microscope (Figure 3-B) and interpreted that the blades had minimum wear and were possibly used to only cut soft material like vegetation or animal skin. It’s possible that these blades were used in ceremonies rather than as day-to-day utility tools. There’s currently and on-going study of the Bijou directed by Dr. Johnson, so maybe we’ll have more definitive answers someday.

Figure 4----Buffalo bones and corn cobs. A) Microscopic close-up of butchering cut marks on a bone. B) Representative corn cobs. Illustration slightly modified from Johnson (2023).

The people who lived in both the Great Oasis and Oneota cultures hunted buffalo and farmed corn; there’s a record of both activities along Kanaranzi Creek. More than 50 pieces of bone have been collected on the Farm and the archaeologists have identified distinctive fractures or cut marks that indicate butchering (Figure 4-A) on eight of them. Twelve bones were burned suggesting that they may have been cooked. Two pieces of bone sent to specialized labs for radiocarbon dating produced dates of 1250 AD and 1770 AD (see the blue arrows on Figure 2). The older date approximates the time that the Great Oasis culture was active. But the later date doesn’t help the case for an Oneota component because the Blood Run occupation fits between 1250 and 1770.

The corn cobs (Figure 4-B) present an even more troublesome dilemma. Some 15 cobs have been collected from sand bars along the Creek although most came from a single site designated as 21RK19 located about a quarter mile downstream from 21RK82. The archaeologists measured and described the cobs, including counting the rows of kernels. All of the cobs have between 6 and 9 rows; modern corn cobs have 12 or 16 rows. However, two cobs that were sent in for radiocarbon dating gave dates of after 1950. That means that either the cobs are from some modern variety that resembles ancient corn or that the dated material was contaminated. Maybe the corn cobs didn’t erode out of a cache pit exposed in a steep Creek bank, but both Great Oasis and Oneota sites have documented corn storage in cache pits. Hopefully, some more lab work will clarify whether the corn is ancient or modern.

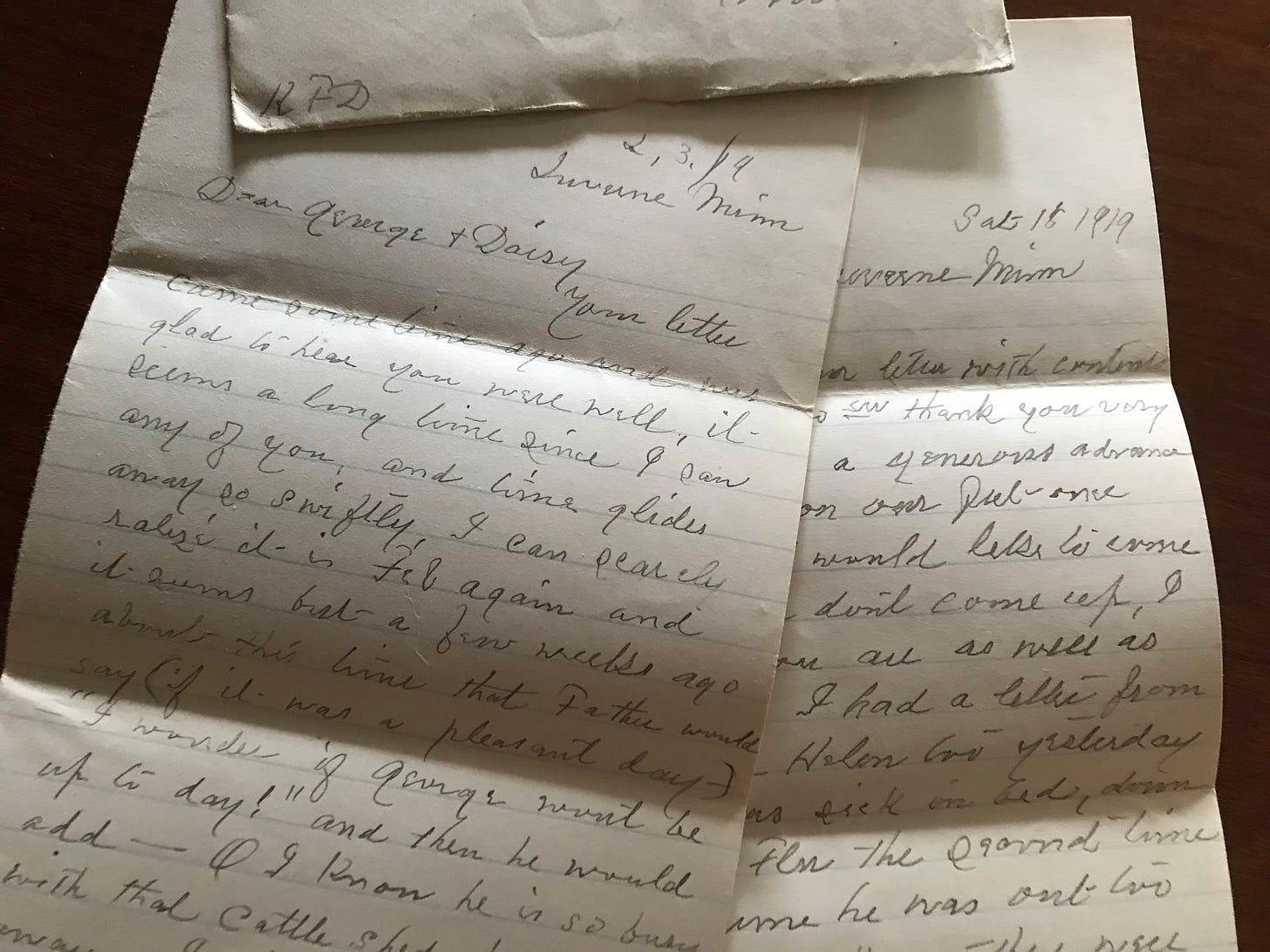

Figure 5----Family letters written by Hattie Shurr in the early 1900s.

Oneota and Great Oasis cultural traditions weren’t the only ones that butchered buffalo and grew corn. The Dakota also engaged in these activities for generations. We have a record of Dakota families camping and traveling along the Kanaranzi Creek in letters (Figure 5) written by Hattie Shurr to family members who had moved to North Dakota. She was the woman who homesteaded the Farm and who met with the Dakota people who were there in the 1870s. So, we have stories about the settler children playing with and visiting Dakota children in their camp. There are also stories about the adults interacting: Great-grandma Hattie sharpened a knife for a visiting Dakota man; the Dakota asked Great-grandpa John to buy supplies because the traders would cheat them; and a Ho Chunk (Winnebago) hunter tracked a wounded elk north from Sioux City, Iowa.

Today, corn is still cultivated and grazing cattle still provide meat from along Kanaranzi Creek. The settler culture is just the most recent one to occupy the area of Lone Tree Farm. Human occupation of this ancient campsite extends back for thousands of years and has left a record in the “multicomponent archaeological site” shared with us by the Creek.

In the next post we’ll look at the regional context for this ancient campsite and talk about some implications for travel and interactions between distinctive lifeways to the northeast and southwest of the three-county area that constitutes the Land at the Edge of the Sky.

In Gratitude:

Our family really appreciates the enthusiasm and interest as well as the cooperation and hard work that Dr. Phyllis Johnson and the staff of the Augustana Archaeology Laboratory have brought to this project. Their efforts have lifted us up from the excitement of simply finding the artifacts to a more nuanced understanding of the stories that the Creek is trying to tell. Thanks also to Phyllis and Margaret Shurr who read an early version of this post.

References Cited:

Henning, Dale R. and Schermer, Shirly J., 2004, Artifact Analysis, in Central Siouans in the Northeastern Plains: Oneota Archaeology and the Blood Run Site, Dale R. Henning and Thomas D. Thiessen (eds.), Plains Anthropology Memoir 36, p. 435-523.

Johnson, Phyllis S., 2023, Analysis of Artifacts Recovered From Sites 21RK82 and 21RK19 on Lone Tree heritage Farm, Rock County, MN, prepared by Archaeology Laboratory, Augustana University, Sioux Falls, SD, 23p.

Jones, Avery, 2022, “Hdihunni” in City of Hustle: A Sioux Falls Anthology, Jon Lauck and Patrick Hicks (eds), Belt Publishing, p. 36-38.

Thanks, Jill. It's a process of mutual education! I didn't get a chance to comment on your boarding school piece last week, but there was also the same level of granular detail that was in your post today. We're obviously "enjoying the fruits" of each others' research.

This is fascinating research and the creek is telling you a LOT about the past. The corn cobs discovered are interesting to think about. I hope you learn more about them. I hadn't realized the importance of arrowheads to dating methods. I keep learnng more.