I’m giving the Place that is the subject of this newsletter a specific name that reflects the location. As we saw in the previous post (Preparation), the area is at the intersection of a ridge of buried red bedrock and the main stem of the Big Sioux River. However, in a larger context, it’s on the transition between the tall grass prairie to the south and east and the short grass and mixed grass prairie to the west. To the north and east, there’s the lakes and forests associated with the footprint of the last glacier. As we’ll see in the next post, this confluence of perspectives is the inspiration for the Place name: Land at the Edge of the Sky.

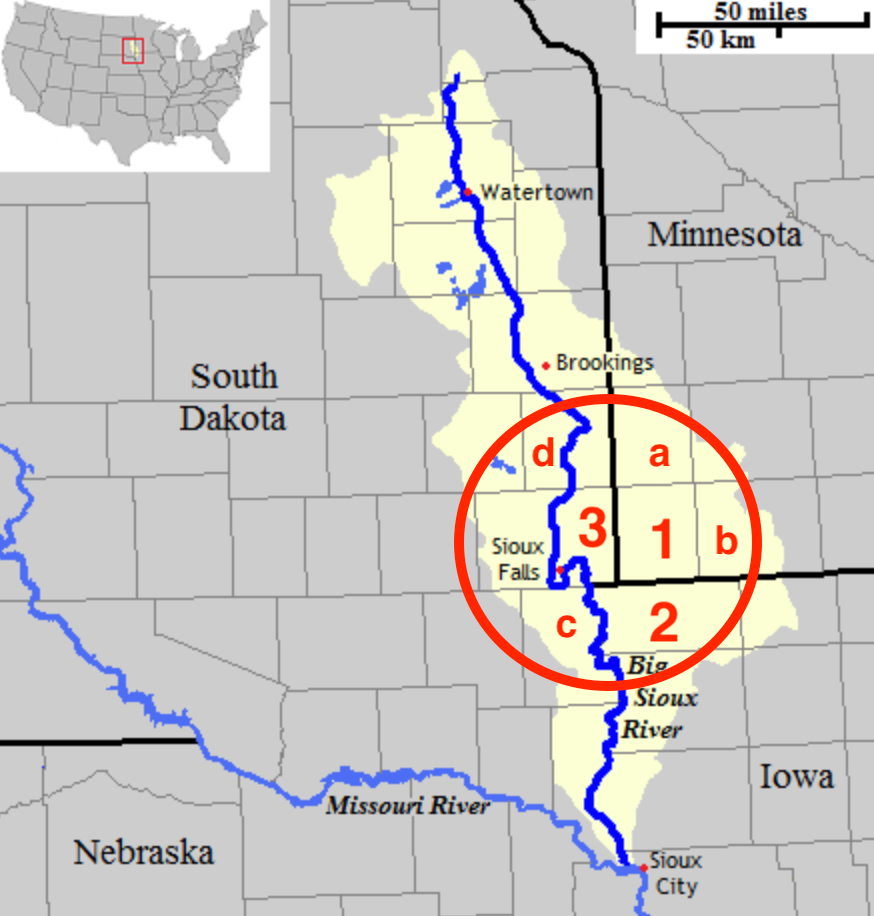

The name of the Place is rooted in its location and when we’re giving the location of a place, we commonly use the names of states and counties. So, we’ll start with what’s familiar: the Land at the Edge of the Sky is located in southwestern Minnesota, northwestern Iowa, and eastern South Dakota. More specifically (see Figure 1, below), it includes all of Rock County (1), Lyon County (2), and Minnehaha County (3) as well as parts of Pipestone (a), Nobles (b), Lincoln (c) and Moody (d) Counties. That defines a location in the middle of the US Midwest….or as one of my favorite local folksingers used to say: “The heart of the heartland”.

Figure 1----Location of the focus area within the Big Sioux Watershed.

Although these artificial state and county lines may be important politically, they have absolutely no significance in terms of the ecology and geology of the area. In a similar way, these imaginary lines were drawn by newcomers and they didn’t mean anything to the communities and families living here before the surveyors laid down the political grid. The descendants of these people still live here and still speak Dakota which is a language of the Land.

Figure 2---The middle segment of the Big Sioux with Blood Run (1) and Lone Tree Farm (2).

Dakota place names often describe what you would see if you were standing in that location. A good example is where the Big Sioux River bends to the northwest just south of Brookings (at the upper red line in Figure 2). The present-day town of Flandreau, SD, is at this location and that place is called Wakapa Ipak’san (Bend in the River) in the language of the Land.

The Dakota words clearly reflect the geology in that area. Upstream, the state geologic map (Marten and others, 2004) shows that the river valley spreads out into a broad, flat floodplain associated with deposits from meltwater streams that flowed eastward off the west side of the last glacier. In contrast, to the south the river flows over the glacial deposits from an earlier ice sheet and the channel is much farther away from the margin of the younger glacier.

Wakapa Ipak’san also marks a change in the plants and animals that live along the river. Biologists (Ley and others, 2022) have taken the bend as the boundary between an upper river and a middle river segment. Each stretch has distinctive populations of trees and birds. The southern boundary of the middle river segment (lower red line in Figure2) is near where the Wakpa Inyan (Rock River) joins the Big Sioux. The approximate course of the Rock River is shown as the thin blue line that extends back to the north through Iowa and into Minnesota.

At the middle of the middle river segment, the Big Sioux makes a distinctive double bend at Sioux Falls, SD (see Figure 2). The Dakota named the falls Mnihaha (Curling Waters) and they call the town site Inyan Kabdeca Otunwe (Shattered Stone City). Just southeast of Sioux Falls, there’s an important archaeological site at “Blood Run” National Historical Landmark and farther east along the Minnesota/Iowa border our family farm is located along Kanaranzi Creek (red stars 1 and 2 respectively in Figure 2). There’s controversy about the names of both of these places.

“Blood Run” National Historic Landmark in Iowa takes its name from a small stream that runs through the site. In a classic case of stereotyping Native American sites, many people assume that there was a battle here. In reality the opposite is true. Archaeological studies indicate that there was a large complex of villages, fields, and burial mounds. There was no defensive palisade around this regional trade center and violent conflicts probably were not an important part of the life of the community and the families that lived there. In a partial response to concerns about the misleading implications of a battle, the state park on the South Dakota side of the river is called “Good Earth”. That’s undoubtedly a more accurate representation of the lifeways that dominated the site.

Kanaranzi Creek is a tributary to the Rock River in southeastern Rock County, MN. Kanaranzi is probably an Anglicized version of a Dakota word that translates as place where the Kansa were killed; so maybe there was a battle near here? The controversy about the name doesn’t come from the Dakota translation, but rather from the “translations” that have floated around the area for generations. My Grandmother used to say that it meant “runs as the crazy man walks” which is an accurate description of how the meandering steam channel wanders across the floodplain. A more recent version, however, says that it means “runs as the crazy woman walks”. Ironically, that’s even more politically incorrect because it’s concerning for mental health advocates and also disrespectful of women’s rights.

These local controversies about the names of places are pretty low-key compared to the excitement several years ago around re-naming Harney Peak as Black Elk Peak in South Dakota’s Black Hills. It’s almost a joke that the name change involved going from a famous old white guy to a famous old Native guy. That’s funny because I’ve been told that the original name of the peak was actually Hinhan Kaga Paha (Made of Owls). It describes what you would see if you were actually standing there. The tourist attraction called “The Needles” (resistant granite pinnacles eroding out of fractured metamorphic rock) associated with the peak really do look like a bunch of owls sitting around the area. At least when the name of Lake Calhoun in Minnesota’s Twin Cities was changed to Bde Maka Ska (White Earth Lake), they used the original Dakota name rather than substituting one old guy’s name for another old guy’s name!

But, the process of assigning names is important and it does warrant some intentional formality. With that in mind, I’m designating the three-county area inside the red circle in Figure 1 as the study area and setting for stories that will be coming to you in this newsletter. And, further I’m naming the area as the Land at the Edges of the Sky (based on the inspiration described in the next post).

Thanks to Avery Jones for his expertise on the Dakota language. He’s a traditional knowledge keeper, linguist, artist, and craftsman from Flandreau, SD. We’ve worked together on several projects and I’m grateful to have him as a friend.