If this is the first post that you’ve read about the Land at the Edge of the Sky, you can find about the location of the place here.

Heads up! This piece starts out with lots of science stuff! But if you stick with it to the end, you’ll find an example of how the Land itself seems to exert a direct influence on people….both indigenous and settler societies. That shouldn’t be a surprise because it’s all part a planetary self-regulating system. However, it’s cool to see an example like this right in our own backyard, rather than in tropical rainforests or polar icecaps!

There’s a concept in geology called “Uniformitarianism”. (Doesn’t it seem like scientists invent words that provide a code for demonstrating that they’ve had technical training?!) The simple statement of the idea is this: “The present is the key to the past”. However, I had a prof in grad school who turned that around to say the “The past is the key to the present”. He worked with rocks that were deposited by mats of algae on coastal mud flats and he would visit modern mud flats to look for specific features that he saw in the ancient rocks. The past geologic record guided what he looked for in the present-day environments.

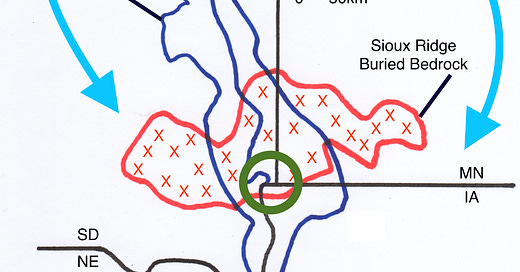

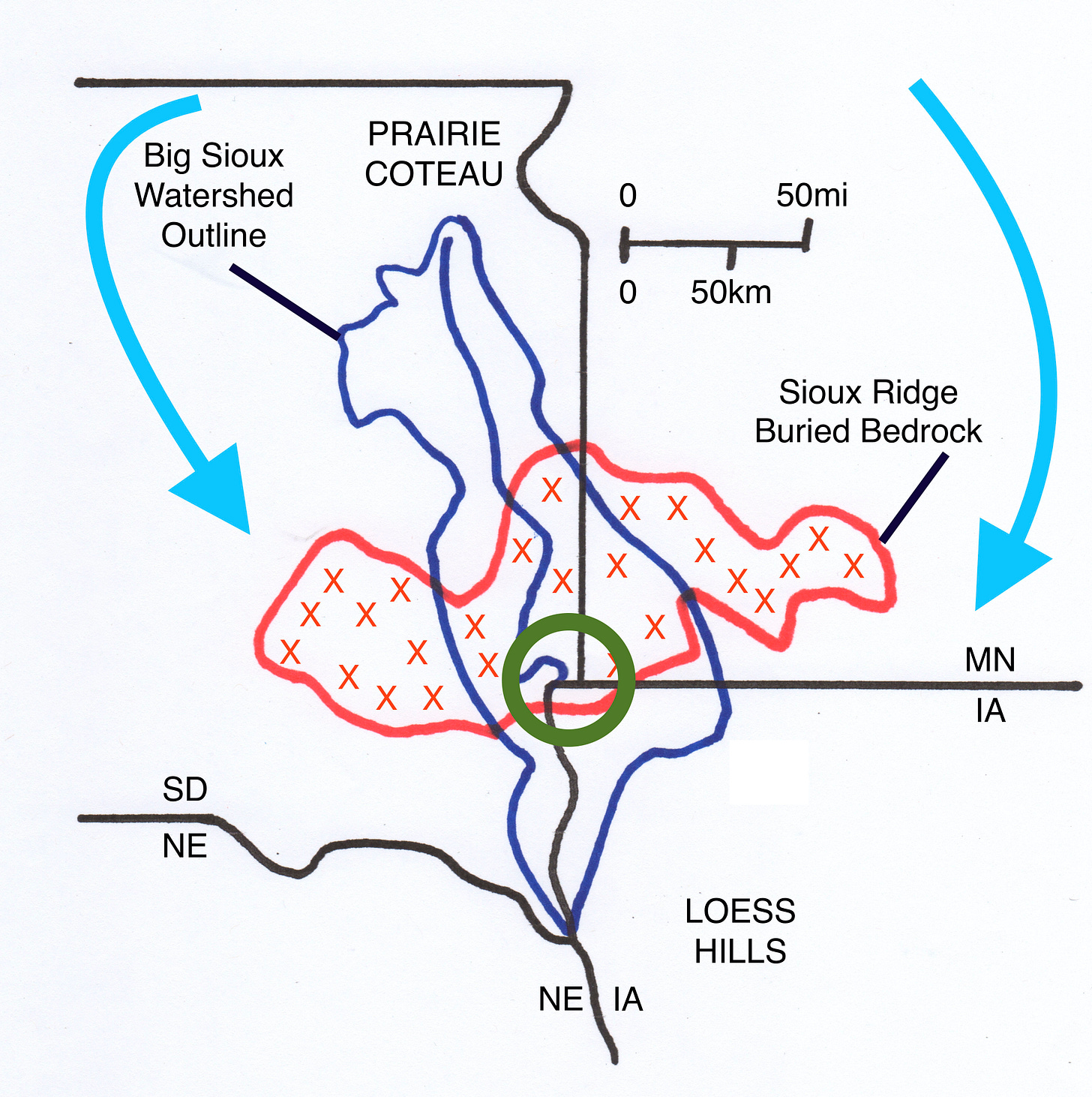

That can be extended to say that the past shapes both the present and the future. And when I say “shapes” I mean that literally. In the Land at the Edge of the Sky there’s a buried ridge of ancient resistant red rock that appears to have provided a template that influenced the paths of glaciers and meltwater streams. Those patterns are in turn reflected in the ecological arrangement of plants and animals which subsequently influenced the activities of both indigenous and settler societies.

Figure 1. A generalized map showing the extent of the buried bedrock ridge and the shape of the Big Sioux Watershed. The movements of two separate glacial lobes are shown by blue arrows and the Land at the Edge of the Sky is shown by the green circle. Modified from Shurr and Henning, 2017.

This map pattern of Sioux Ridge looks different than the outline of exposed bedrock that we saw earlier because that just showed the very top of the buried ridge. Publications describing the geology of Lincoln and Rock Counties ( McCormick and Hammond, 2004; Bauer, 2020) show that at Blood Run the red quartzite is buried about 200 feet below the surface and at the Farm it’s at least 500 feet down. Abrupt buried cliffs characterize the sides of the ridge at Blood Run, but the slopes are much gentler near the Farm. Although the local areas have different specific details, taken together the pattern of the buried Sioux Ridge probably altered glacial routes and thus indirectly influenced environments for plants and animals.

The outline of the Big Sioux Watershed approximates the system of glacial moraines that define the Prairie Coteau. The main stem of the river was an ice-marginal stream that is unique where it flows across the bedrock ridge. In this central area, the fractured rock controls the double bend and influences the channel geometry within our focus area. The valley has different aspects upstream and downstream from where it crosses the buried bedrock ridge and the populations of plants and animals reflect those differences in the valley environments. But the local differences are also part of larger regional patterns of distinct ecologic areas.

The life sciences, like the earth sciences, have “code words” to reflect the technical training. According to Wikipedia, an “ecotone” is a transition between regions that can be characterized by specific communities of plants and animals. Figure 2 shows that the Land at the Edge of the Sky (marked by the green circle) is located in one of these transition areas called an ecotone. The dark blue region to the north and east is the Great Lakes and Upper Midwest; it’s a region of lakes and forests. The light tan area (labeled with a 4) to the south and east is the Eastern Tallgrass Prairie and Big Rivers; it generally corresponds with the contemporary corn belt and is also called the Prairie Peninsula. The pink area (labeled with a 13) to the north and west is the Plains and Potholes region; the eastern part is closely related to the glaciated lakes and the western part is shortgrass prairie. The yellow area ( labeled 7) is the Great Plains and is also mainly shortgrass prairie.

Figure 2. Generalized ecologic regions mapped and named as a part of a Federal program called “Landscape Conservation Cooperatives” (Google it to get the whole sad story of bureaucratic ebb and flow). However, these LLCs are also good for demonstrating the transition between communities of distinctive plants and animals.

The distinctive and characteristic plants and animals originally hosted people who had different lifeways and cultures geared to the respective environments. The Great Lakes had communities that harvested wild rice and hunted deer while in the Eastern Tallgrass Prairie, communities grew corn and hunted buffalo. This wasn’t necessarily a hard and fast distinction; corn and buffalo were used in the north and deer were also hunted in the south. But the differences did accentuate the transitional nature of the Land at the Edge of the Sky and people moved back and forth through this transitional ecotone. The curved green arrows in Figure 2 are meant to be a stylistic representation of those movements.

The indigenous cultures associated with the lakes and forests in the northeast and with the rivers and prairies in the southeast did interact in a fairly peaceable way across the east-west crest of the buried rock ridge. The area was not a firm border, but rather a permeable membrane where people and trade goods, as well as ideas and ceremonies could be exchanged in a relatively “neutral” territory. It’s not like there were never any conflicts and clashes, but in general it was to everyone’s advantage to cooperate and to share. The Land itself provided the model. Mitakuye Owasin: “All my relatives.” And, Wicoweciwazi:“We are related through sharing”.

In contrast, the buried east-west ridge of resistant red rock and the associated north-south highlands of the Prairie Coteau may have been a buttress against the onslaught known as “Manifest Destiny”. The buried east-west of resistant bedrock acted like the bow of a boat cutting through water. The juggernaut of the colonial settler culture charging in from the east, seemed to split around the Ridge.

Early wagon trains that probed across the central plains in Nebraska stayed to the south and so did the transcontinental railroad that followed them. Up in North Dakota, the right-of-way for a later transcontinental railroad was driven through the northern plains and the later development of oil and gas and coal never really made it down into the South Dakota. This “wake” of settlers’ routes around the front of the bedrock ridge is shown as generalized curved green arrows in Figure 3.

Figure 3. The main routes of settlers headed west split around the Land at the Edge of the Sky (shown by the green circle) and consequently the area of major Native American reservations was protected from the onslaught The map shows tribes recognized by the US government and is available from the Bureau of Indian Affairs. I modified it by adding the green circle of our focus area and the arrows to illustrate the speculation about settler migration routes.

However, the transitional ecotone along the crest of the buried bedrock ridge did more than deflect the paths of in-coming immigrants. It also seemed to insulate large portions of South Dakota from the earliest stages of land appropriation. As a consequence, Native American reservations are larger and more numerous in South Dakota (see Figure 3) than in any of the adjacent states. It's almost as if the Land itself provided the protection that produced a haven for the last vestige of the indigenous resistance to the encroaching colonial settler culture.

I don’t have any “hard data” to test this notion that the Land protected the indigenous cultures. But maybe the date of organization for individual settler counties in the five states would show a supporting pattern?

The past informs the future.

The subtitle of this piece is also a paraphrase of the title of a book by Dakota scholar and historian Nick Estes: Our History is the Future. It was the One Book South Dakota selection in 2022 that looks at how indigenous lifeways provide an outline for how the US settler society should modify its approach to Nature. That guidance is also the model for how these newsletters will be constructed: we will look to the past (rocks and water, plants and animals, indigenous and settlers) for perspectives on the present and on the future.

This exploration will start after the first of the year with a series of essays that focus on the complex of archaeological sites on both the west and east sides of the Big Sioux River in South Dakota and Iowa. This huge mosaic of individual communities centers on Good Earth at Blood Run. This series will be followed by a series of posts that describe recent archaeological work in the much more limited area, specifically our multi-generational Lone Tree Farm.

Happy Holidays!

I am taken by the notion of the land itself offering protection from encroaching settler culture. Thanks for an interesting read and history that goes back even further of this Midwestern region than I had previously known about.